Navarin

nothing remains

25/07/10 18:35 Categorised as: Holidays | Summer 2010

of the Ferme de Navarin. Neither of the village of Perthes-lès-Hurlus.

But the site of the ill-fated farm is all too conspicuous: the site now of a Memorial, and an Ossuary. One of the most moving things we’ve either of us seen, and we saw it on a suitably grey day.

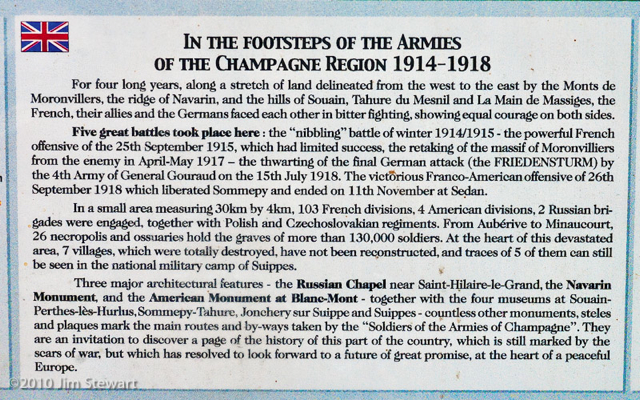

The D977 north-east from Chalons towards the Ardennes crosses the flat and rather featureless terrain of Champagne, and beyond the town of Suippes traverses a shooting-range still used by the French army. On a crossroads about 3 miles north of Suippes is Souain-Perthes-lès-Hurlus, This reconstructed village occupies the site whereon was destroyed the village of Souain. The once-nearby village of Perthes-lès-Hurlus survives only as a name appended in a manner ironically reminiscent of the French villages’ habit of appending the name of their finest vineyard, as in Nuits-St. Georges, or Puligny-Montrachet.

Souain-Perthes-lès-Hurlus has barely 10 inhabitants for each letter of its name.

Both Souain and Perthes-lès-Hurlus were destroyed in the ravages of of the First World War.

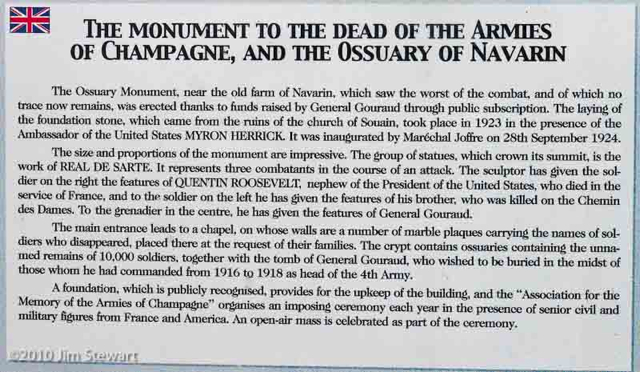

A couple more miles north up the D977 we reach the site of the Ferme de Navarin, now the site of the Memorial and the Ossuary of Navarin, where lie the bones of 10,000 fallen combatants of the French, German, American, Russian, Czechoslovak and Polish armies who fought for four years over a front 30 kilometres long and no more than 4 kilometres deep in the Battle of Champagne, 1914-1918.

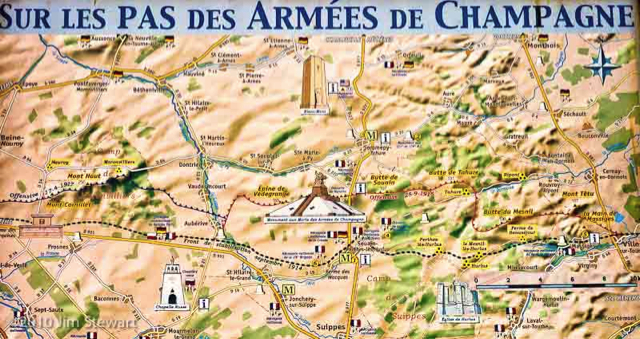

The map above shows the positions of the front line, and the minimal scale of its movements, between 1914 and 1918.

A little work back home turns up some interesting context on the Navarin Monument, its place in history and those of its creators.

The figure in the middle of the statue is General Gouraud, who commanded the 4th army in the Champagne/ Marne battlefield on and off from late in 1915; undertook the final, successful, offensive in September 1918, and led the project to build the memorial. The sculpture itself is the work of Maxime Real del Sarte, an active member of the far-right Action Française group, and a leader of their youth movement Les Camelots du Roi. So there is perhaps, in this monument, and in del Sarte’s sculpture, some undertone of triumphalism, of the spirit of reparation that blighted Versailles and led to the collapse of German democracy into Nazism.

Nonetheless, it is impossible not to be moved by standing in the boneyard of Navarin, where the landscape still seems to bear the pock-marks of the shell-holes in which so very many died.

Comments